The Writer Who Draws: On the Ink and Art of Apollonia Saintclair

- Dante Remy

- Aug 31, 2025

- 18 min read

Dante Remy |

“Let us not confuse the question. Apollonia Saintclair is not the artist behind the pen. She is the threshold, the channel, the voice that draws.”

The Introduction I Wanted to Write

Let me tell you from the start: I am going to get this all wrong. But that, in truth, is the essence of Apollonia Saintclair’s art. Her drawings are not made to be “understood” in any final sense. They are riddles that multiply as you look, images that demand stories but never yield conclusions. Every attempt to name them only opens another chamber of ambiguity. What follows, then, is not a map but a wandering. It is my story woven into her ink—just one among the thousands her work has already provoked, and the thousands still to come.

An Introduction The Artist Deserves

There are artists who illustrate, and there are writers who narrate—but Apollonia Saintclair belongs to neither camp. She is the writer who draws, a conjurer of stories in ink, who lets the unconscious guide her hand like a sleepwalker in shadow. Her black lines are not decoration but sentences; her compositions are chapters torn from a secret novel of desire and strangeness. She does not render bodies so much as she reveals fictions in flesh: wounds that are ecstasy, embraces that are estrangements, gazes that belong as much to the viewer as to the viewed. To look at her work is to feel both seen and unsettled, as though she has reached inside your private dream and sketched it before you could speak it.

Much has been written about her emergence and mercurial rise on the internet in 2012. And yet, to want to know her story—her past, her identity, who she is outside the page—is to risk missing the point. That search gets in the way of knowing her art. In this essay I focus not on her biography but on her drawings, and the stories they summon. So let us agree to disagree, if we must, about the desire to unmask the artist. Instead, let us turn toward the illustrations themselves, and the voices they release.

The first shock of her art is not erotic but literary. Each drawing is a story compressed to a single moment, like a page torn from a book whose remaining chapters exist only in your imagination. When I see her ink, I do not think of other illustrators but of writers: of Flaubert’s obsessive detail, Matheson’s haunted estrangements, Kafka’s dense shadows. She does not draw to show; she draws to narrate. Each stroke of blackness is both sentence and silence, a fragment of fiction that calls upon the viewer to complete it. Her works are not fantasies but worlds—laconic, labyrinthine, and alive.

What makes them unforgettable is the sense of estrangement that hovers over every line. Her drawings are never quite safe: they belong to the liminal terrain where beauty unsettles, where pleasure bends toward pain, where intimacy dissolves into something uncanny. They resist the simple comfort of desire and instead open onto that landscape where fascination and repulsion entwine. Her eroticism is not a call to arousal alone, but a threshold into strangeness—a reminder that to be seduced is always to be unsettled.

And yet: you will never know who she is, and you should never seek to know her. Saintclair is not the subject of these images but their conduit; her anonymity is not a mask to be stripped away but the very condition of her art. To demand her face would be to mistake the door for the world it opens. What matters is not the life she lives once she steps back into the ordinary, but the vision she offers us in the extraordinary. She belongs to no biography but the one you discover in her work—our work, because when you see yourself mirrored in her ink, the story is no longer hers alone.

Her genius lies in this: she makes art that is at once intimate and impersonal. The women and men she conjures are not characters but archetypes—desire itself in shadow, the body as myth, the gaze as confession. Cross-hatching behaves like syntax: density for emphasis, white space for breath. In her hands, sexuality is not spectacle but scripture, written in ink that refuses erasure. To look is to be implicated, to be turned voyeur and visionary at once. She is not offering herself but a mirror, and if you dare to look long enough, you will see not her secrets, but your own.

This is why her work cannot be contained by the familiar language of erotic art. The erotic is certainly there—sometimes violent, sometimes tender, sometimes absurd—but it is always bound to something more elusive. Like the gothic novelists who made terror sublime, she reminds us that the deepest pleasures are threaded with unease, that beauty is most potent when it hovers near the grotesque. Her ink insists that to desire is to risk dissolution, that to look is to risk being changed.

Saintclair also has a sense of irony that cuts like a scalpel. Titles, captions, and the sly humor embedded in her compositions make it impossible to take her images as straightforward fantasies. They undercut sentimentality, expose absurdity, and remind us that desire is never pure. The laugh that emerges in front of her work is not the laughter of mockery but of recognition—the sudden awareness that our longings, however transgressive, belong to the human comedy. It is precisely this irony that allows her art to reach so many: it reassures the intellect even as it unsettles the body.

But what lingers most is her mastery of ambiguity. She works in black and white, yet nothing she creates is one-dimensional. Every drawing carries at least two readings—sometimes three or four—layered like transparencies. To stop at the first interpretation is to betray the work. These are double-bottomed drawers, and to open them is to discover not closure but further recesses. She teaches us that eroticism, like truth, is inexhaustible: it only deepens the longer you gaze.

In an age where everything clamors to be explicit, her anonymity and her indeterminacy feel like acts of resistance. They remind us that mystery is not a defect but a force. She does not give you herself; she gives you the conditions in which you must give yourself away. Her drawings leave you implicated, unsettled, laughing, desiring, estranged. They make you wonder not who she is, but who you might be, once the ink has spoken to you.

So let us not confuse the question. Apollonia Saintclair is not the artist behind the pen. She is the threshold, the channel, the voice that draws. She has built for us a literature of shadows in which words have vanished and only their images remain. She has offered us a mirror to see ourselves differently, to glimpse both our hunger and our strangeness. To encounter her art is to discover that anonymity can be more intimate than confession, and that the deepest truths are revealed not when the mask is torn away, but when it is worn with absolute conviction.

La femme au fichu blanc (Happiness blooms in my garden)

A walk through just a few of the thousands of works of art helps to reveal the nature of Saintclair’s appeal: the way her drawings linger in the mind, multiply into stories, and haunt us long after the page is turned. One such image, first posted on social media and never collected into her books, is titled La femme au fichu blanc—“the woman in the white headscarf”—with the English subtitle, Happiness blooms in my garden. The title alone sets the paradox: serenity and mischief, innocence and exposure, leisure and provocation entwined in a single frame.

A woman sits on the steps of a modest garden dacha, or what appears to be so, legs open, sex revealed, her expression faintly amused. The stone still holds the noon heat; the leaves behind her hum with insects. She could be anyone: a holiday guest taking the sun, a hostess waiting for company, a stranger who has wandered in from another life. The headscarf, the bare feet, the rustic stone steps all suggest simplicity, leisure, even innocence. And yet—her body tells another story. Her pubic hair is neatly trimmed, marked with the worldliness of the city, a sign of the curated, the intentional. She is not simply a child of the garden; she has carried a different kind of knowledge into this place.

At her feet sits a small dog, upright and calm, as though posing for its own portrait. The dog’s presence complicates everything. If it is her dog, then the moment is one of intimacy made banal: an ordinary afternoon with a companion who knows nothing of scandal. If it belongs to a friend, then the scene shifts—she is borrowing not only space but loyalty, exposing herself in a borrowed intimacy. And if it is her lover’s dog, the question sharpens still further: does the animal stand in for its absent master, a surrogate placed exactly at the threshold of her desire? Her smile may be amusement at her own audacity, or at the absurdity of this new companion suddenly elevated to co-conspirator.

From here, a thousand narratives unfold. Is she a woman escaping the city, savoring the freedom to sit unguarded in the sun? Is she a seductress, smirking at the scandal she knows she provokes? Is she laughing at us, the viewers, for seeing only exposure where she feels none? Or is her amusement directed inward, at the strangeness of being caught between cultivation and rustic ease, between the world of the city and the world of the garden?

But here is the revelation: none of this is interpretation in the scholarly sense. It is storytelling—my own story, projected into her ink, made necessary by the way her art refuses to close its meaning. Saintclair does not give us images to decipher like puzzles with solutions. She gives us fragments that demand our invention. What I see is not the truth of the drawing but a fiction I cannot help but write in response.

And that, perhaps, is her rarest gift: she does not simply show, she provokes narration. Her followers do not merely view her images; they inhabit them, tell themselves into them, fill the silences with their own voices. Each drawing becomes a mirror that speaks back, not with her story, but with ours. To look at her work is not to decode, but to compose—to become the author of a fleeting novel written through her lines.

The depth lies in that paradox: she is the artist, yet we supply the stories. She sketches the body, and we write the life around it. That is why her art feels so endless, so inexhaustible—because it multiplies itself in the imagination of every viewer. La femme au fichu blanc will never belong to one reading, but to a million. She is not her, she is us. And that is Apollonia Saintclair’s gift: to turn spectators into storytellers, to remind us that our erotic lives are already scripted—and the body is just another page.

Le masque de la Méduse (Object Woman)

Let us open Volume 4 of Ink is My Blood and gaze upon an image. At first encounter, the drawing overwhelms: a woman collared, gagged, and engulfed by a monstrous apparatus of dials, lenses, and levers. Her eyes are hidden behind a phantasmagoric optician’s device gone berserk, while her mouth is pried open, drooling around a ball-gag. Flesh is consumed by mechanism; body becomes extension of machine. She is not simply masked—she is transformed into Object Woman.

The French title, Le masque de la Méduse, invokes the petrifying gaze of myth. Yet here her gaze is eclipsed, redirected through glass and metal. Is Medusa subdued, her terrible power neutralized by optics? Or has the machine become her mask, a new face multiplying her vision, freezing us with its mechanical stare? The English title, Object Woman, sharpens the paradox: she is objectified, reduced to instrumentation—and yet in that reduction she radiates uncanny power.

Her sexuality is blunt, but it is also displaced. The gag stretches her mouth, saliva trailing from her lips, but her face is not contorted with panic. She seems transfixed, suspended, as if caught between pain and rapture. Perhaps she is not resisting the apparatus at all. Perhaps she is absorbed by what she sees—images refracted endlessly through the lenses, a world only she can perceive. The drool becomes less a mark of degradation than of surrender, of immersion in an experience we cannot access.

This is not simple bondage. It is fetish as allegory: the union of body and machine, silence and spectacle, submission and transcendence. The labels on the device—“CAUTION,” “DO NOT REMOVE HELMET,” “RESCUE OTHER SIDE”—mock us with their warnings, as though there were some protocol to follow, some safe way to engage with what is essentially a riddle.

And so, stories multiply. Is she victim, bound within a patriarchal machine? Or is she priestess, chosen to see what others cannot? Is her silence imposed, or is it the price of a vision so overwhelming that words would falter anyway? Her enjoyment is ambiguous, but it is there—quiet, disquieting, a complicity that unsettles the boundary between domination and desire.

Or is this simply a modern, even futuristic Medusa—the woman whose crown of vipers has been replaced with technology, whose mask of lenses petrifies us more surely than serpents ever could? In this reading, she is no longer trapped at all: she is the captor. We, the viewers, become the frozen statues, transfixed and transformed by her mechanical gaze. Her power lies not in her own expression but in our inability to look away. We want to create a modern retelling of the Medusa story from this image because we must; the gaze has captured us, compelled us to narrate ourselves into its mythology.

What Saintclair captures is not just the spectacle of restraint, but the allure of surrender to something larger than oneself. The image forces us to confront the strange intimacy between vision and control: how to look is also to be trapped, how to desire is also to risk petrification. We do not know what she sees behind the mask of dials, but we know she does not wish to look away.

That is why Le masque de la Méduse remains one of her most iconic works. It resists the easy reading of victimhood or titillation. It confronts us with a deeper unease: that pleasure may dwell in restraint, that revelation may require objectification, that the act of looking is itself a form of entanglement. We are caught with her in the machine, transfixed, transformed, unable to step back.

La technicienne de surface (Worshiping My Idol)

Turning the pages of Volume 4, we stop at a scene that seems absurd: a woman, skirt hitched, panties tangled at her thighs, bends forward to kiss and press against an enormous poster of another woman’s body. Her hands are braced on the surface, as if she might step through it or draw it around her like a lover. In the corner, a vacuum cleaner slouches idly, anchoring the scene in comic domesticity, as though housework has been interrupted by desire.

The French title—La technicienne de surface—literally “the cleaning lady,” a bureaucratic euphemism that strips dignity away in favor of sterile neutrality. The English title, Worshiping My Idol, transforms the same image into an act of reverence, longing, even transcendence. The interplay is striking: one diminishes, the other elevates. One reminds us of labor’s banality, the other of devotion’s rapture. Caught between the two, the figure becomes both ordinary and mythic, comic and tragic.

Is she mocking the rituals of idolization, parodying our dependence on images larger than life? Or is she entirely serious, lost in reverence before an unreachable surface? Is she a beautiful, perhaps tragic cleaning lady who has paused from her work to kneel before a private fantasy? Or is she every viewer, caught in the paradox of worshiping that which cannot worship back? The vacuum cleaner suggests interruption, yet it also functions as a sly joke: even in the most mundane corner of life, ecstasy can erupt. The hose coils like a leash no hand is holding.

For some, this is comedy, a parody of desire’s absurdity. For others, it is longing distilled, devotion played out on an unyielding surface. Saintclair does not allow us to choose; she holds both readings in tension. Worship and parody blur together until they become indistinguishable.

And this is her rare genius: her images are not puzzles to be solved but fictions that demand completion. Each viewer writes a different story. For some, she is a cleaning lady made radiant in her longing, her devotion tragic in its impossibility. For others, she is a mirror of our own absurdity, pressing ourselves against surfaces that will never yield. Which is true? All, and none. The drawing is not singular—it multiplies. And in its multiplication, it makes storytellers of us all.

La lionne blessée (Love is a Killer)

Let’s turn to another iconic illustration in Volume 4, Love is a Killer, its English title. In French it is La lionne blessée—“the wounded lioness.” Immediately, the pairing of languages fractures the image into two readings. One is mythic: a creature of ferocity and dignity, a lioness who bleeds but does not bow. The other is brutal, intimate: love itself as executioner, passion as wound. Both titles hold truth, both contradict one another.

The drawing itself is deceptively stark: a woman’s face in close view, her features taut, caught between suffering and rapture. Arrows pierce her flesh, but her gaze does not falter. She seems suspended between collapse and transcendence. The French title emphasizes her power even in woundedness; the English title underlines the cruelty of love’s bite. Which are we to believe? Or are we meant to oscillate endlessly between them?

Here the stories multiply. Is she victim of desire’s violence, or its willing acolyte? Do the arrows represent betrayal, loss, heartbreak? Or are they the ecstatic marks of being possessed by love so entirely that the body itself must rupture? Perhaps she is not victim at all but predator wounded by her own hunt, a lioness who knows that to love is also to bleed.

And perhaps it is no mistake that la petite mort—the little death—haunts the face: orgasm and arrows layered as one. To see both ecstasy and death mingled here is to recognize that Saintclair draws not just wounds of the flesh but the paradox of pleasure itself: that rapture and ruin are inseparable. These arrows pierce as much with desire as with violence, collapsing climax and mortality into a single haunting image.

Saintclair forces us to supply our own narrative, to read the arrows as allegory. Some will see tragedy, others resilience. Some will read in her face the exhaustion of surrender, others the power of endurance. The genius lies in the impossibility of choosing. She offers a single frame that holds a thousand unwritten chapters.

And so the truth of the piece is not her truth, but ours. Each viewer completes it with their own memories of desire, betrayal, devotion. This is not interpretation in the narrow sense, but storytelling compelled by the image itself. Saintclair’s art reminds us that we are already authors of our erotic scripts—that the body is another page, and love, when it wounds us, is always both killer and gift.

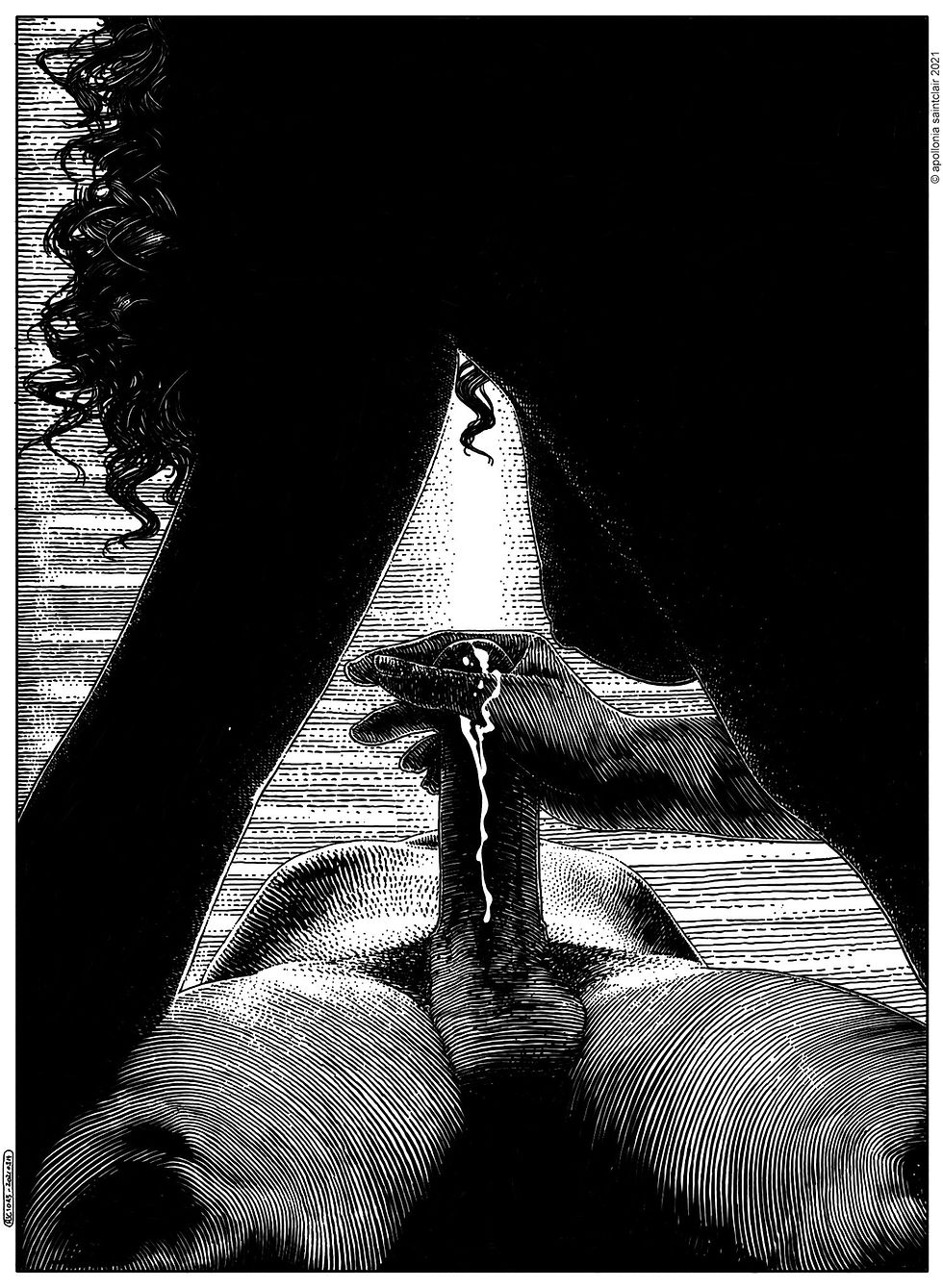

La Musique du Matin (Head)

At first glance, the image seems brutally direct: a woman leaning over a man’s body, her hand tight around him, semen spilling in a pale thread. Sex, immediate, unvarnished, raw. It could almost be mistaken for blunt pornography—until we read the title. La Musique du Matin, “the morning music.” And suddenly the image shifts.

Now the drawing is not only something we see, but something we hear. The music is not metaphor alone—it is the rhythm of their pleasure. The slick chorus of fluids. The low moans. The sharp intake of breath. The percussion of bodies moving against one another. The hand gripping him keeps tempo; the drip of semen is both note and rest; the man’s body beneath her hums with bass. The music is the build to climax, the crescendo of release, and the long decrescendo after—the calm, the silence that follows orgasm like the last chord dissolving into air.

This is why the scene lingers. What looked like blunt carnality is revealed as score, as ritual, as performance. The shadows no longer merely conceal—they become the stage against which sound vibrates. The curls of her hair fall like commas in the dark, punctuation in the unspoken hymn of sex. The body becomes not just page but instrument, tuned to the intimacy of the hour.

And morning complicates everything. Morning is both aftermath and overture: the hour when night’s secrets still cling, and the day has not yet begun. To call this “the morning music” is to suspend the act between conclusion and renewal, a climax that is also a beginning. Pleasure becomes time itself: brief, cyclical, irrepressible.

The power of the piece is this transformation. We begin with an image of sex, stark and unyielding. But with its title, Saintclair asks us to listen—to recognize that sex is never silent. Its sounds are its truth: the gasps, the moans, the music of bodies saying what words cannot.

And that is the morning music: not only the act itself, but its echo. A hymn written in flesh, in sound, in silence. We smile when we see it, because the music is already ours. We know it.

We’ve heard it. We’ve been there—in the slick rhythm of bodies, the laughter under breath, the rush to climax, the collapse into warmth. We want to be there again.

It is our music, our sex, our morning. Saintclair reminds us of what we already carry: the memory of desire’s song, waiting always to play again.

For Your Love is Better than Wine (Project M)

It is, of course, impossible to select only a few images to represent Apollonia Saintclair’s work. Her output is too vast, too prolific, too profound. Each piece multiplies into stories of its own, and the reader should seek out her active site to experience the full breadth. Yet here we glimpse something new—an image that heralds her long-anticipated Project M, titled For Your Love is Better than Wine. If her six volumes of Ink Is My Blood mapped an atlas of desire in ink, this next work promises to be monumental: a liturgy of flesh and imagination.

The image is stark yet elusive: a nude woman kneels in a small stone chamber, a candle in her hand, an open book balanced on her lap, surrounded by a constellation of flames across the floor. A cross hangs from the wall, asserting faith, but the shadows and nudity turn the act into something between devotion and transgression. The light across her face is not a blindfold but candlelit chiaroscuro—an invitation to see her in fragments, as if caught in mid-revelation.

But who is she? Is she aristocracy, reading enlightenment texts under cover of night? The pastor’s daughter, or even a nun, hidden in a cloistered library with forbidden books? Or is her reading the spoils of a tryst, her body traded for access to knowledge, her nudity less about shame than transaction? Each possibility expands the story outward, refracts it into new genres: romance, tragedy, liberation, rebellion. Saintclair plants the seeds, and we, the viewers, write the garden.

The title reaches back to the Song of Songs: “For your love is better than wine.” Love as intoxication, devotion as rapture. This biblical resonance complicates the scene further. Is she reading scripture? Casting a spell? Writing her own gospel in the silence of her body? Is the candle an instrument of prayer, or an erotic offering? The details sharpen the ambiguity: the shoes neatly placed aside suggest deliberateness and choice, while the vessels in the corner evoke ritual preparation. Every element pushes us toward a story, but none closes it.

In Project M, these images are paired with brief, poetic passages—slender texts to accompany the drawings. This fusion will shatter the boundary between illustration and literature, blowing open the possibility of novels that will not be written by the artist alone but in the minds of her viewers. Each pairing becomes a spark, an unwritten book living inside every witness.

That is the promise: Saintclair no longer simply gives us pictures to interpret. She sets text beside image, teasing us with fragments of story, daring us to fill the rest. The result will be a cathedral of multiplicity: erotic, sacred, heretical, poetic. For Your Love is Better than Wine will not close her oeuvre but detonate it outward, leaving us with a thousand novels we will each carry away in silence.

Where She Exists, We Begin

Let us end here, struck by the magnitude of an art that will not be contained. To stand before Saintclair’s work is to feel both excitement and disturbance at once—as though the same lines that seduce also threaten to undo us. Her images function like maps of half-dreamed fears and desires, charts of places we seem to know but cannot name.

She exists in our world only through her drawings. Each figure, each moment she offers in her place is inked in her blood, a condition of her vision. That is why every mark feels at once intimate and estranging, like touching someone you cannot fully see. This is the way she inhabits us: not as a name or a face, but as a pulse carried through line and shadow.

In her work, we witness perpetually beginning. Each drawing holds us in a moment that is before, during, and after all at once—an eternal present I cannot name. Are we watching the instant before desire erupts? Its ferocious fulfillment? The messy aftermath? We do not know. What we know—but dimly—is that we will return to the image, over and again, like a ritual of seeing, and every time, we will be changed.

The novels Saintclair whispers into the world are in her lines and our imaginations. If you want to see more—if you want to be both unsettled and carried away—visit her site. Explore the six volumes of Ink Is My Blood in French and English, with essays from fellow wanderers of desire and shadow. Look for Project M, poised to dissolve the boundaries between drawing and poetry. Seek out her exclusive offerings—signed prints, collector’s editions, original sketches—each not a possession, but a threshold into a story you must write.

We arrive searching for her and leave searching for ourselves.

Full Disclosure: I’m a Storyteller Too

I must disclose, though perhaps it is already obvious, that I do not stand outside Apollonia Saintclair’s work. I write as Dante Remy—but like thousands of others across the world, I have followed her from her earliest days online, and I own her volumes and her artwork. Perhaps it is because I am a writer that her images strike me as literary, that her drawings feel less like illustrations and more like stories. Yet I know this recognition is not mine alone—it is the strange communion she extends to all who dare to look.

There is more. Her drawings have crossed into my own work, appearing in Bloodlust and gracing the pages of my novel The Mysteries: I Misteri del Convento, a tale of forbidden passion in a Sicilian convent at the turn of the century. In those books, her figures did not simply illustrate but deepened the vision, shadows answering words.

So let me be clear: this is not a conflict of interest, but the deepest form of interest itself. What I have written here is not critique, but another chapter in the story. It is an attempt to honor what her drawings give: profound realities and impossible riddles, revelations that dissolve into mystery, and a vision of desire as inexhaustible as ink itself.

Learn more about the artist, her art and art books at apolloniasaintclair.com. Look inside and learn more about the books The Mysteries and Bloodlust published by and her art in Erosetti Press at erosettipress.com.

©️2025 Dante Remy

Comments